This is not just a set of free plans for a working model steam engine. It’s a well-written, well-organized, profusely illustrated 113-page tutorial about machining metal.

If you’re an inexperienced machinist who at least knows the basics I would strongly encourage you to download these plans and build this engine. Don’t let the picture fool you – this is not a difficult engine to build. It will definitely take some time and patience, but if you follow Bogstandard’s step-by-step instructions I think you will probably find it’s not as hard as you might think. By building this engine you’ll learn a lot more than you would by making the typical “wobbler” engine many beginning machinists often build. You’ll also acquire the confidence you need to tackle much more complex machining projects.

There are two more reasons for building this engine. First, it was intended to be made inexpensively out of junk or scrap materials. So it probably won’t cost you a lot, even if you’ll have to buy all the metal for it. You’ll also find that Bogs tries to help minimize the cost of tooling by suggesting cheaper alternatives when he can. The second reason is that you’ll be able to find help if you have questions or need some advice. The designer is well known for sharing his knowledge and experience and I’m sure that if you have a question, he or one of his friends will try to help you.

I am not a beginner anymore, but I’m not that experienced either, so I’ve decided to start building it when I finish the Stirling engine I’ve been working on. I think I’ll learn a lot because Bog’s tutorial is full of techniques and methods that I’ve either never tried or haven’t practiced much.

The plans use metric units, which could be an issue if you’re in the US or another country still using the Imperial system. I’m in the US (upstate NY) but I don’t think it’s a big problem. I’m building an engine now from metric plans and most of the time I just convert the dimensions to inches and machine the metal to whatever size that is. But I have had to substitute SAE sizes for fasteners and threads because I don’t have much metric-size tooling. I’ve also had to make some substitutions when I’ve wanted to use standard-size material, like drill rod for shafts. Those substitutions require a little bit of extra thought and planning, but it’s not a big deal.

“Bogstandard” is a pseudonym for John, the engine’s designer. He can regularly be found on the MadModder forum. He was also on the Home Model Engine Machinist forum for a long time and you can find a lot of his writing there. I don’t know why John picked the name he did, but I do know that he goes out of his way to share his knowledge and help others, and he does it with a wonderful sense of humor. I’ve learned a lot from his posts, which almost always include lots of good photographs illustrating what he’s talking about. When I asked him for permission to make his plans available here for download he said:

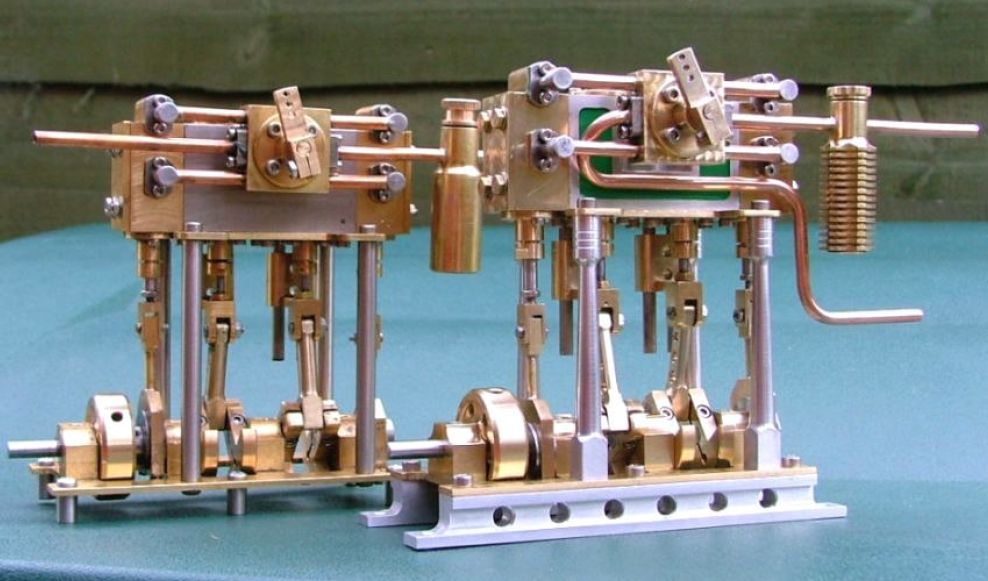

John’s design is for a marine style twin-cylinder slide valve steam engine that could be used to power a model boat. It’s about 4.5-inches high, about the same in length and about 2-inches wide. It’s known as the “Paddleduck” engine because it first appeared as a series of posts on the Paddleducks steam engine forum from May to July 2007. The construction of each part is described in a simple and easy-to-understand manner. Bogs also includes the answers to questions that others had, along with some of the suggestions and comments he received. Here’s an excerpt where he describes how to finish the cylinder bores:

Reaming the Block Holes

I said last time that we had finished with the blocks for the moment.

I forgot that not all of you will have the means to get a good enough finish on the bore: they will most probably vary from a slightly dull surface, thru what looks like screw cutting to digging out the hole with a hammer and chisel.

If you can borrow a reamer, and your hole is still slightly undersize, use one, otherwise this is how I would get an acceptable finish. You can go out and buy adjustable laps, but that costs a lot, just to get a couple of holes cleaned out, this isn’t the totally correct way but it will be better than what you’ve got at the moment.

Start with the largest hole, stick the last drill you used through them and wiggle about side to side, the one with the biggest wiggle is the biggest hole.

Mark the largest hole with a felt tip. Now chuck up a piece of material to make the lap out of, have it sticking out of the chuck by 1.5 times the length of the hole plus 25mm (1″), I use hard nylon but aluminum or brass will also suffice, I get better results with the softer materials.

Carefully (no heavy cuts here, material sticking a long way out of chuck) and turn down the rod until it just pushes through the hole for a length of 1.5 times the length of hole (like Pic 13).

Carefully (no heavy cuts here, material sticking a long way out of chuck) and turn down the rod until it just pushes through the hole for a length of 1.5 times the length of hole (like Pic 13).

Now we need to spend a bit of money unless you are from the old school and have some in your garage. We need to buy some fine and coarse grinding paste, Halfords is about the cheapest at about £3 and you get a grinding stick with that as well. This quantity will last you for the rest of your life.

Dab a bit if the coarse stuff along the length of the lap, you don’t need a lot. Get a piece of hardwood and with a rolling action in combination with turning the chuck by hand (you have stopped the lathe I hope) embed the surface of the lap with grinding paste, what you are doing is making a very accurate round file.

Select the lowest speed on your lathe and switch on. Keeping well away from the chuck feed the hole to be lapped onto the lap, get ready to let go on this initial feed in just in case it bind up and sticks. If all is well the lap will be turning (without you going round with it) in the hole. Now just gently move the block up and down the lap in a sort of rotary twisting motion. You need to keep the lap fully into the hole at all times.

Change the block position 90 deg around the lap every so often, eventually you will get the feel and a rhythm going.

Do this for a couple of minutes, stop machine and check the bore, it should have started to smooth out. Repeat as necessary, wipe off, recharge, turn the block around and come from the other end of the hole, until the rough stuff has gone, then wipe off coarse grinding paste with white spirits and recharge with fine. Repeat the operation.

You should after a while end up with a nice round, parallel bore showing slight scratch marks on the surface, these scratches will help the bedding in process as they retain oil while the pistons and bores are wearing against each other.

Clean off the grinding paste and turn down the lap to fit the smaller hole, and repeat the process again. When finished give the bores a very good clean out to get rid of any remaining grinding paste.

If you remember from before, the pistons are going to be made to fit the bores, so they don’t need to be the same size.

Put the lap you have just made in a safe place, you might make something else where you can readjust the size and use it again. I will do the pistons in the next article; it will give time for the batteries to recharge on my camera.

In addition to a large assortment of tips and tricks, Bogs covers topics such as safety, engine turning, climb/conventional milling, turning eccentrics, drilling deep holes, silver soldering and more. Again, I’d like to suggest that you download the plans and at least take a quick peek at them.

Download The Plans

Individual Chapters (PDF, 1.6 – 3.7 Megs)

Chapter 1 – to page 14. Includes the Table of Contents

Chapter 2 – pages 15 – 29

Chapter 3 – pages 30 -45

Chapter 4 – pages 46 – 60

Chapter 5 – pages 61 – 73

Chapter 6 – pages 74 – 84

Chapter 7 – Appendix 1/Part A – Design Sketches, pages 85 – 100

Chapter 8 – Appendix 2/Part B – Design Sketches, pages 101 – 113

All Chapters

Zip File (22 Meg)

Self-extracting File (22 Meg)

DXF/DWG Component Files (18 Meg, self-extracting) – Richard Harris and Nigel P. Henry took Bog’s hand-drawn part sketches and created DXF and DWG files that can be opened by almost any CAD program. If you don’t have one then you can use the free viewer they included. Bog’s hand-drawn plans are pretty good bu if you would like a more formal set of drawings then get these. They can also be used to construct the engine using CNC machines.

Related Links:

YouTube video of the Paddleduck engine running

Blogwitch’s (Bogstandard’s) YouTube Channel

Another Paddleducks build log (MadModder.com)

Thanks, I’ve been looking for something just like this. I’m a 60 yr old forced into retirement Machinist. On Dec 16th last year I had my second open heart surgery. This time they replaced my aorta valve and did a single bypass. I have a small shop next to the house with a couple of small milling machines and lathes. I have thought about making a steam engine for years. I stumbled upon the set of plans and knew this was for me. It’ll be a month or more before the wife let’s me back into the shop. But by then I’ll know these plans back and forwards. Thanks for giving me one more thing to keep me going. Rick

I’m known as oldgeezerwnc on valvereplacement.com drop in and take a look at my photos and you’ll see why these plans are giving me a plan, a plan to recover.

I came across a 30-page PDF by “Shred” which documents the construction of his Paddleduck engine. It’s well written and profusely illustrated. You’ll probably find it useful if you’re going to build one of these engines. You can download at:

http://www.homemodelenginemachinist.com/index.php?action=tpmod;dl=item251

Tried clicking on site listed by Rob above got this message:

What happened when Google visited this site?

Of the 30 pages we tested on the site over the past 90 days, 4 page(s) resulted in malicious software being downloaded and installed without user consent. The last time Google visited this site was on 2010-10-14, and the last time suspicious content was found on this site was on 2010-10-12.

Malicious software is hosted on 2 domain(s), including 77.78.245.0/, 77.78.246.0/.

1 domain(s) appear to be functioning as intermediaries for distributing malware to visitors of this site, including 77.78.245.0/.

This site was hosted on 1 network(s) including AS3595 (GNAXNET).

Just so everyone understands, Rick is talking about a warning that Google is issuing about the Home Model Engine Machinist Forum, NOT MachinstBlog.

I experienced the same thing Thursday night. I could not get Firefox to ignore its warning long enough for me to find out what’s going on. But I just tried again and I found a message from the owners saying they were experiencing a problem and it wasn’t a mistake or false alarm. That message was posted on October 8th and that’s all I know. I’d stay away until Google says it’s OK.

It’s one of my favorite forums and I know the owners would never knowingly cause harm to anyone’s computer.

Could you please answer these questions as I am a beginner to this hobby,

These engines while simple and made from inexspensive materials seem very simple and crude and I hope that i’m not insulting anyone if I say that they look very roughly made. I assume the maker only has very limited facilities, perhaps a few hand tools and pillar drill? If not I think that they look very poor. If I were to make an engine, even from scrap I think that I would take pride in how it looks.

Kerv

Are there better plans available than these please, somewhere i could start and make prettier engine?

Kerv

Do you realize that the “Paddleduck” is model of the type of maritime steam engines that were popular over 100 years ago? Also, that the engine was designed and built to teach machining techniques to newbies and help develop their confidence? Did you look at the dozens of pages of construction notes, photos and helpful tips?

Any engine that a beginning machinist, such as yourself, could realistically build is probably going to look crude. I think the knowledge and skills that you will acquire by building this engine are much more important considerations than its looks.

The Paddleduck engine may not be a good first project for a new machinist, but it is probably an excellent second or third project. I don’t consider myself a newbie any more, but I’m also not that experienced either. So I may build it because I think I’ll learn a lot from “Bogs,†who is very well liked and respected for his willingness and ability to teach new home machinists.

One more thing. It’s not a very good picture of the engine and I was not impressed when I first saw it. It also doesn’t give a good indication of its size. Since then I’ve seen other pictures and now I think it is a nice looking engine. Although it is a steam engine and not everyone likes them.

it looks like the centerline of the base plate in the DWG is 1mm out. Also it is 52mm wide, but in the hand drawn sketches it is only 50mm. Is there a reason for this, or is that an error?

We’ve struggled to the part where we make the crank shaft webs, but we can’t seeem to struggle past this point. We can’t make good enough webs.

Firstly, our parting skills are miserable. We make dishes rather than disks. Yes, evrything’s locked down, and the gib strips are tight, and the tool is as far in as it will go, and perpendicular, and the work is as close to the chjuck as we dare, and the tools are new and sharp and centred, but still it whails as though on the point of self destruction, and the cut surfaces are not flat and not smooth. It’s not the matal bar stock either, we tried it on another bar. The first part went perfectly, with no noise and no drama – the second one, about half an inch further down – and we’re back to the wailing banshee.

“But wait, there’s more!”

The jig you propose John, is puzzling us. You seem to contradict yourself in describing it’s construction and use. Should we have it upside down using the holes in it to guide the drill? We’ve tried it like that and also the other way up, using the milling machine’s table to measure the distances (which seems to render the jog pointless) – but we have no success.

Our first problem was he dishing on parting as described. We can get it good enough, we think. Stressful, and not pretty, but functional.

The next problem was that the webs would not tighten on both shafts at the same time. The central shaft would tighten up but not the outer one – or vice versa. We solved that by drilling out to half a mil less than final diameter and reaming the last part.

The next problem is that – no matter what we do – we can’t get the webs to pinch up on the shafts perpendicularly. They’re always a little out, and of course, the errors add up across the shaft and the thing won’t turn. We’ve made four sets of webs so far. Since the holes are (now) made in a milling maching, everything is rock solid and (we thought) guaranteed to be upright – so we’re at a loss. The bar is straight, the holes are clean and snug. They’re just not upright. The milling machine’s quill seems to be upright when tested with a square on the bed aganst a straight bar coming from the chuck.

Any insights from anyone would be greatly appreciated. At this point, we’re thinking of taking up cross stitch :o)

You are lucky Chris, I found your comments by accident whilst trolling thru the site.

But anyway, I will attempt to get you back on the straight and narrow.

To answer your query about the crank webs.

I state that these are about the most critical bits, and my fault really, I should have gone into more detail about how I get them all perfectly parallel sided and with the holes exactly in the middle.

Before parting any of the disks off, you should have faced the end of the bar. That at least gives you one side exactly square to the OD. It doesn’t matter at all about the shape of the other side, as long as you have enough material left to bring it to the correct thickness.

I am lucky in that I use soft jaws in my chucks, but you can get the same results by using a ‘pot chuck’. Similar to the bottom one shown in the top picture on this link. It needs that outside step to ensure it presses against the chuck jaws squarely.

http://www.gadgetbuilder.com/MiniMods.html#PotChuck

You would insert your faced of side into the chuck and clamp it up, then face the rough side until it is the correct thickness. Before removing it from the pot chuck, drill (and ream if you have one)the centre hole to 5mm (or whatever size you are using for the main shaft), deburr centre hole both sides. You should be able to do hundreds of these discs, all the same thickness and all having parallel faces, plus the holes should be spot on centre.

Pic 49 on page 24 shows how the holes should turn out.

Now to the drilling jig shown on page 25 as pic 50.

Get yourself a bit of say 1/4″ thick steel (just to stop the drill cutting the holes larger) by say 1″ wide and 3″ long.

Put it into your milling vice and about half way across the 1″ side and half way down it’s length, drill a hole that will allow you to loctite or stick a piece of the rod you are using for your main shaft. Then step along your jig from the centre of the mainshaft hole, 10mm, and drill a 4mm hole (ream if possible). Go back to your mainshaft hole and step the other way 8mm and drill the 2.5mm hole, not really critical on that size, somewhere near enough is fine, as long as you have a piece of good fitting rod to go into the drilled hole.

How to use. Follow the numbers on the jig picture.

1) Obtain yourself a piece of very close fitting rod to go into the small hole.

2) Fit one of your now accurately turned and drilled discs onto the centre pin.

3) Turn the assembly over so that the drilling guide holes are at the top, and then the disc is sat onto two parallels, one either side of the centre pin in the vice, then tweak it up, but not enough to put flats on the side of the discs, just enough to hold it.Then drill thru the small hole with the correct sized drill(2.5mm). You really do need to make sure your mill is trammed correctly, to make sure that the drills go thru square

4) Then push your thin pin into the hole you have just made, thru both the jig and disc

5) Because you now have in effect two pins going thru the disc and locking things in position, you can now drill the 4mm hole.

6) Remove disc and repeat with another one. You should end up with discs like in picture 49, where you can get all three rods going thru all discs.

Now onto the slitting problem, where they will not clamp up tight and square.

Hopefully, by using the jig, all holes should now be square.

Material used will also play a part here. If you are using a hard material such as steel, it may not be able to deform the disc enough if your two main holes are slightly oversized or not square. I would definitely recommend brass for these parts if possible, if not, then aluminium, but that might distort and loosen over time.

I don’t know if you are using a slitting saw or hacksaw for doing the slot, but the slot really does need to be across the centre of all holes, or very close to it.

BTW, the slot is done after the disc is shaped with the counterbalance and before the clamp screw hole is done. Do the shaping as in pictures 52 to 54 on pages 26 and 27.

I do hope that this bit of text has put you back on track, if not, then let me know and I will see what I can do for you.

If you lived within striking distance of Crewe, Cheshire, you could come over to my shop and see how it is done.

John

Hello John and many thanks for the time you have given us, which of course, is in addition to the time you took to make the plans and the BLOG in the first place.

Where should I have posted these comments? I’ll put them here, and maybe also in a forum.

We made the jig exactly as you described, and the plate is really tough “hot rolled†thick steel.

We do face the webs before parting, so there is one nice square face, and one groovy dishy one, and we initially used the jig in the way you describe – “upside down†– peg down between the jaws of the post drill vice. Then manually guided the drill into the holes in the thick steel plate of the jig, and down into the web.

Which way up should the web go? I guessed good side down – where it will sit on the drill vice squarely. We didn’t face the bad side as we couldn’t see a way to hold it. Your pot chuck idea is new to us, and perhaps we could make one, and use it to make new webs, but I don’t understand what the benefit would be beyond cosmetic. (that’s just a literal statement of my ignorance – not a contradiction of your advice!). In addition, since parting is such a noisy and stressful process, the prospect of putting my head near the lather through four more of them is very daunting.

Later on when our post drill-and-jig-upside-down method proved inadequate, we dumped the jig, and used the milling machineՉ۪ table to drill accurately.

We are slitting with a hacksaw, and after the web is shaped, and I have to say it’s a carve-up. Not straight, not central, and not consistent between webs. I don’t know how we would do better. But we thought this wasn’t important – what seems to be important is that we make a gap to allow the straight, parallel sides of the holes to pinch on the shafts, thereby holding them in correct registration.

You say: “Hopefully, by using the jig, all holes should now be square.â€

The central issue is that, simply, they ain’t.

And we don’t know why nor how to fix it.

We are using steel as recommended. We could use brass, but since it’s softer, I would have thought it’s more prone to allow deviations from true. The parting off could be more fun though…

Your offer of a visit is very kind indeed John, thank you. However, we live 150 miles away which is a six hour round trip, not including any “shed timeâ€.

Perhaps the answer lies in tramming – I’d never heard of that phrase before. We did check that the quill was true – or seemed to be – but thinking about it, it was very crude – putting a rod in the chuck, and assessing its squareness visually, against a set square placed on the bed.

Another engineer suggested making the crank with the shaft all in one piece, glueing iti n place, then removing the unwanted parts of the shaft. I can see how this would true up the shaft segments, but the idea of relying on glue to hold a shaft in alignment in a hole which isn’t true seems very dodgy, and also, removing the unwanted shaft segments would seem far from trivial. In any case, it would not help us with trueing up the big end segments of the crankshaft.

We’ve also considered using square rods in place of the webs, and doing away with some of the bearing blocks to give us more room for a more chunky design.

Also, as I mentioned, criss stitch is looking very attractive.

If you have anything to add, John, we’d love to hear it, but if you’re out of ideas, then elt me thank you once again for all the time you have given us.

Best Wishes,

Chris

These plans are really great, but I’d like clearer drawings. I downloaded the CAD files but the self-extracting zip isn’t working on Linux for some reason. Is there any reason you can’t just stick them up to download directly?

Belay that last comment. The very latest 7z seems to handle it. Although it does seem unnecessarily exclusionary to make it a Windows-specific format.

Also, for anyone else having trouble: The trial version of QCad is able to open these files. But printing might be a hassle. You can switch to landscape on A2 and it’ll fit, but you’ll need to either tile it or get a big printer to get it output.

If anyone is looking for the PDF of Shred’s build log mentioned above, which is helpful since photos are no longer displayed on the thread, it’s currently here:

https://www.homemodelenginemachinist.com/threads/paddleduck-engine-by-shred.29195/

Scott