This essay by “Mikey” is the winner of our “Machining Metal as a Hobby” contest. The object was to tell visitors about home machining and try to get them interested in doing it as a hobby. I think he wrote a wonderful essay and I would like to thank him for taking the time to enter the contest. — Rob

“Hmmm … this isn’t as easy as it looks.” I had just taken the first cut with my new lathe and the piece of aluminum rod I was cutting looked like a rough rutted road instead of the nice shiny surface I thought I would get. The noise and vibration didn’t thrill me, either. I eventually figured out that the speed control was actually important, as was the feed wheel I had so merrily cranked. After a few tries I finally got a mirror finish on that part but I realized that I had just flunked Metal Cutting for Dummies, Special Ed Division.

I didn’t set out to be a machinist, hobby or any other kind. I simply had a whole slew of other interests that I was involved with and machining was supposed to be a supporting activity. I realized that it was a major advantage to be able to repair almost anything, make something that is difficult to find or doesn’t even exist, or improve something that could be made better. So rather than make do, I decided to make parts. At least that was the intent.

This was 13 years ago and my interest in machining has turned into my main hobby! My other interests have taken a definite back seat and I’m happy to say that while I never intended to be a hobby machinist … that is what I am.

So, what happened? What could be so interesting about this hobby that it can keep someone engaged for more than a decade and put all his other interests on a back burner? I think it’s because you’re always learning. You see, hobby machining is not just about machining. Its also about understanding your metals and other machineable materials and how they like to be cut, tools, tooling, cutters and their geometry, coolants and chemicals, heat treating, electricity and electronics, physics, geometry and trigonometry, hydraulics, machine design, and a myriad other subjects. This pursuit of knowledge is driven by each project you do or problem you need to solve. Before you know it, you know a lot about a lot of things! This enriching experience coupled with the ability to make just about anything is really what keeps this hobby so interesting.

Whenever people ask me what I can make on my machines I answer, “Oh, just about anything.” They always look puzzled because “anything” covers a whole lot of territory. So here is the honest answer – you can make almost anything from just about any machineable material that fits within the working envelope of your equipment. If you need a custom part such as a hose adapter with metric threads on one end and SAE threads on the other, this is easily done. Need a mandrel to make a pen on your lathe? Make the mandrel, slip the wood onto it and turn the pen. Model cars, model engines, steam engines and incredible locomotives are made by hobby machinists all the time. How about parts for an invention you have in mind, or an adapter to fit a special lens onto a camera it normally wouldn’t fit? The possibilities are seemingly endless and, once you learn how to machine stuff, you can make them.

I will tell you up front that this is not the cheapest of hobbies because you will need to buy some precision machine tools and their related accessories, precision measuring tools, and materials to make stuff from. Depending on the size of the equipment you choose this can range from affordable to very expensive. Most of us purchase a basic package to get us started and buy accessories and other tools as needed so that the cost is spread out but the cost is still there.

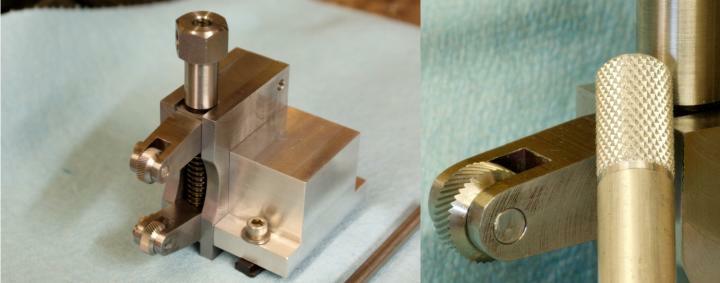

Is it worth the cost? Absolutely. In fact, while your equipment will cost you up front it can save you a lot of money in the long run by allowing you to make things that may be quite expensive. My last project was an interchangeable-tip live center. The commercial version of this tool runs about $1500.00; I made mine for about $25.00 and it is every bit as accurate as that expensive commercial model (they don’t even make one to fit my lathe). The cost of this tool alone would have paid from my lathe and my mill!

I also recently repaired a kerosene-burning clothes iron. It was an heirloom owned by a friend and the brass pump handle had snapped. I was able to reproduce the handle, repair the piston and it fired right up. It now sits on a shelf next to her grandmother’s picture. You can’t put a price on the smile I got from her!

There have been so many situations where being able to make something has salvaged a broken item or vastly improved the function of something that it’s hard to list them all but you get the idea. So, what does it take to do this stuff?

At the heart of any machine shop you will find a lathe and a milling machine. These are the two pieces of equipment that enable a machinist to do his or her thing.

The lathe works by turning your work piece while you move a cutter into it to cut it to the size and shape you need, producing a cylindrical object with precise dimensions. Things like shafts, pins, knobs, screws and bolts, nuts – anything that needs to be cylindrical or round. Called the King of machine tools, the lathe is one of the most useful and versatile tools you can own.

With the mill, the cutter turns instead of the work piece. The work is held in a vice or fixed to the table and is moved into the cutter to produce the shape or profile you want. This table is able to move in two axes (side to side and front to/and back), while the headstock that holds the cutter can move in a third axis (up and down). Control of these three axes allows you to shape a work piece into just about any shape you need. The mill is said to be the only machine that theoretically can reproduce itself and most of the work in a machine shop is actually done on this machine.

Each of these machines performs their basic functions – a lathe cuts a cylinder and the mill profiles and shapes. Each machine is able to perform a huge variety of other things by using attachments or accessories that expand on these functions. For example, a lathe can cut a cylinder, which can then have a knurled finish put on it by using a knurling attachment.

Lathes and mills come in a wide variety of sizes, from tiny watchmaker’s machines to gargantuan shipyard machines. The machine is generally chosen to suit the needs of the user. For example, if you live on a farm and must make repair parts for a tractor you need a lathe with enough capacity to do that. On the other hand, if you live in an apartment and your shop is in the spare bedroom then you will need a much smaller machine that you can carry and put away when you’re done. In general, the cost of the machines and their accessories is proportional to their size, and the size of machine is chosen by estimating the largest work piece it will have to work on.

For the beginner this size thing can be a conundrum. How do you know how big a part you need when you haven’t needed to make it yet? I can’t tell you that but it may help to know that I am an average user who lives in a city and makes parts for my own use. I own a Sherline long bed lathe and milling machine to make stuff for cars, machine restoration, welding and woodworking equipment, car audio, archery equipment, lawn equipment, fishing stuff, general repair work – the list goes on and on. For me, the vast majority of my work is under 6″ long and less than 1″ in diameter. I do need to go larger on occasion and my lathe can turn a piece up to 3″ in diameter (up to 5″ with risers) and up to about 15-17″ long. I can turn or cut most materials, from wood to plastic, mild steel to stainless steel, and just about anything in between. I have not exceeded the capacity of my lathe or mill yet but I’ve come really close.

My point is that a small machine – in my case a “miniature” or “mini” machine – is capable of doing the vast majority of the work I need. This class of machine is probably amongst the lowest in cost; there are a LOT of them to choose from and most are available as manual or CNC machines. Rather than go into a description of the field I would suggest doing some homework if you are considering joining us in this hobby. There is a lot of information on the net, in videos, books, magazines and the maker’s websites so you can make an informed decision. Or you can always ask Rob!

Before ending I want to offer a bit of advice about buying precision measuring tools, and only because it is a potential sinkhole. In this hobby you will discover that you can only cut as accurately as you can measure and to measure you need tools. I’m sure you’ve heard of micrometers, vernier or dial calipers, dial indicators and the like. These instruments vary in cost and quality but, in general, you get what you pay for. If I were just getting into machining here is what I would do. Go to the Long Island Indicator Service website and learn about what these instruments do and which ones are the best ones in each category, then go out and buy the best one – and buy it once. You don’t need to buy it from Long Island Indicator Service, though if you do you will find them to be honest and of high integrity. Many of the finest tools are for sale on eBay for a fraction of their retail cost; this is where I would check first.

If you know a photographer with a really good tripod I would bet money they have 3 or 4 cheaper tripods sitting in the closet that more than equal the cost of the good one. Precision measuring instruments are like tripods. Save the money by buying the best instrument for your needs and only buy it once. You will be very glad you did … and don’t ask me how I know this.

I hope this discussion gives you an idea of what this hobby is like. It isn’t just for guys, it isn’t hard to do, you don’t have to be rich or have a huge shop, and you don’t have to be “mechanically inclined.” You can get into it to craft incredible model aircraft or jewelry, carburetor parts … or you can do it to make stuff, like me! You’ll learn a great deal about a wide variety of subjects and the confidence you gain as you hone your skills is priceless. The only thing I can think of that is more fun than this is maybe your favorite Black Diamond ski slope … nope, not even that!

Mikey

2010

Looks like you know a thing or two about Tru-cut. I have a 25 inch 7 blade commercial tru-cut and I’m looking for a service manual for it. It’s about 20 years old and looks just like the ones they sell today. Any help in locating this would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks

Hi John,

I know a lot about the P-20S but have not worked on your mower, which I sounds like it might be the C25 model. I could not find an owner’s manual anywhere for my mower so I wound up calling Tru-Cut and they sent a copy to me free of charge. I suggest you do that. While you’re at it see if they will also send you the Illustrated Parts List for your mower. With that info you can completely rebuild your mower.

If any other questions arise let me know.

Mikey

Mikey,

I too go by the same moniker and, oddly enough, share a lot of your hobbies and passions. Most of my yard equipment has been hand me downs that I’ve resurrected and saved from the landfill. I’ve made parts for them with simple shop tools and have always wished I had a mill/lathe combo.

I’ve been on the verge of being a hobby machinist for a number of years and find your post both comforting, and scary at the same time. My wife is already a “Workshop Widow”, and I fear that plunging myself into this hobby would make her even more so.

I’ve been in the process of building a hobby CNC machine for the past few months and am down to the driver boards. I might have something worthwhile to show for my efforts by Oct or Nov (life keeps getting in the way).

Found your blog via Makezine. Cheers my friend. Happy milling!

Great article and has re-ignited my interest. But once again I founder: There’s a lot of help out there on how to pick a machine, but not much on what else is needed. You mention “tools” including measuring, but don’t really give a comprehensive list.

Obviously you can buy and buy and buy and never be done. But what is the minimum set of tools needed? And what dependencies do they have on each other? (i.e., if I find a bunch of reamers at the flea market that seem to be in good quality, should I get them even though I don’t have a lathe yet? or will I need to know the frobnitz number of the lathe first?)

Hi David,

First, welcome to MachinistBlog! Sorry about not including a “must have” list of tools but it was more an introduction to the hobby. It might be best if we handle this discussion on the forum instead of in comments. That way anyone who wants to contribute, can. I’ll think about a basic list of tools and tooling that will get you started and we can go from there. Will that work?

Sign up as a member of MachinistBlog.com and you can post to the forum. See you there!

Mikey

Hi John/Cementtruck,

Welcome to MachinistBlog! Thank you for your kind words. Its nice to know that there are other guys in the same situation – shop widow, too many interests to count, shop-time deficit, etc. Its also interesting that you go by the same moniker and your first name is my middle one!

I think hobby machining is something us self-reliant types just fall into by default and I cannot think of anything that is as useful or as challenging. If making your own CNC machine is your way of dabbling in machining I would love to see you when you get serious! You might want to post it here so we can see it when you’re done.

Jump in, buddy, the waters fine!!

Mikey

I just wanted to say that I enjoyed your article. I am saving up for my 1st mini lathe now. I relish the idea of making an item with my own hands. It gives oneself a sense of satisfaction when you do what others say is impossible.

Thanks for the kind words. You’re right, doing the impossible is fun but making something that never existed before is even better!

Here’s hoping that lathe gets here soon,

Mikey

Quality posts is the secret to interest the users to

go to see the web page, that’s what this website is providing.

Thank you, Drills, and welcome to MachinistBlog!

I really like your comment about how you can only cut as accurately as you can measure. I personally am not in the habit of milling any type of metal, but my uncle has recently been looking into hiring someone to do some work for him involving CNC metal milling, and I think this would be a good thing to talk with him about. It would seem like a good way to check the quality of a company before hiring them would be to ask about what sort of precision measuring tools they have and use.

Thanks, Luke. If I were looking for a company to do some work I would ask them for a list of references and call them. Nowadays, lots of people do CNC jobs but seeing how they treat their customers, their pricing and their integrity – you’ll get that by word of mouth. Good luck!

Thanks, Mathias. Since this blog has gone dormant I spend most of my time on the Hobby Machinist forum and all of my writing is done there. If you haven’t been to HM, come and visit.

I normally don’t write for other blogs but if there is something specific that you need then we can discuss it.

I stumbled upon this blog while looking for info about something related to machining, (I think). A post about stepper motors caught my eye.

I, too, have a Sherline lathe. I didn’t set out to be a Sherline owner, didn’t even intend to buy one when I did. I’ve been repairing cars since 12, fixing anything and everything, since, and have the kind of extensively outfitted fab shop you can only have after 50+ years.

I have always wanted to be able to ‘machine’ stuff, with a real lathe &/or mill, not substitutiing with anything from a hammer and chisel to saws/drill presses/router table, (I built a 6061 T-6 T-slot table for a metal saw I built using a router table. Once you figure out shimming for accuracy, the rest is ‘cake’… well, campfire jiffy cake, anyway.

I was casually looking for a lathe or mill, and buying tooling and metrology tools, etc in the process, (great deals, only), knowing that’s were the true expense is. Then, I saw a CL post for 30-40 pounds of end mills $35.00.

I about broke my ankle/neck/body getting the seller on the phone, getting dressed and & out the door, all at the same time.

He had 30-40 pounds, alright, the smallest was 0.500 roughing mill, the largest was 1″; 30-40% were brand new, and only ONE was chowdered but salvageable, with a regrind.

I told him they were way more, but he insisted on 35.00, saying they were his deceased father’s, and held no interest/value to him. So, when he asked if I was interested in a lathe, he had my attention, (I thought I could make it up to him on a big purchase, for stealing these end mills.)

He said he’d be right back, and I thought he went for keys to a shop, or shoes… When he came back with this toy lathe, in his hand, down by his knee, I thought he was joking. I would have bet money it was a toy.

He said he wanted 50.00, for it, so I took the opportunity to give him the 50.00, knowing if the toy had no value, I was still waaay ahead on end mills.

That began my education on Sherline.

Fast foreward 8-9 years, and I have been using the Sherline for almost a year. I went the custom route for motor, (missing when bought), installation, and set up. I spent three months watching YouTube vids while bedridden two winter ago, watching Sherline based vids, to bcbloc, whose day job is growing corn for whiskey, and passion/goal is to have the largest lathes/mills/radial drill presses a ‘home shop’ has EVER had, (the last time I checked, his newest lathe was still on the semi flat bed he brought it home on, It is a beautiful art deco Monarch, with just enough room left on 40′ trailer for a couple of tooling cabinets! I’m talking BIG iron.

The common thread between all of them was rigidity, and adequate power. I heard a lot of horror stories about not being able to part on a Sherline, or turn steel, or even use carbide inserts, on a Sherline.

Most Sherline vids are voice overs because the OEM Sherline sounds like a worn out sewing machine, at full speed, and that’s without it actively turning anything.

I took on Sherline rigidity, and short of physical size, and depth of cut, I can do anything on the Sherline, that can be done on a full size lathe.

I have solved the rigidity issue, have plenty of power and can part anything, (using strips of old carbide Skil saw blades as the tooling, yet). I use almost exclusively carbide inserts or brazed carbide. I haven’t found much use, yet, for the 10# pounds of HSS cutters I picked up, cheap.

I am considering putting the parting tool I designed in the market, and fully intend to put the ER32 spindle upgrade on the market when I get the bugs worked out. The next component I’m taking on is an adjustable tailstock, so for turning tapers and leaving the headstock anchored in place.

I saw your note to someone about spending most of your time on the machinist site, (blanking on name), but will try to catch up with you, there, to talk Sherline, machining and fixing stuff, (I STILL fix everything, after 50 years.)

GeoD

Very cool story, GeoD. Sounds like you’re now an accomplished Sherline guy and have found out how capable a machine it is. Come on over the HM if you can. Its a good site.